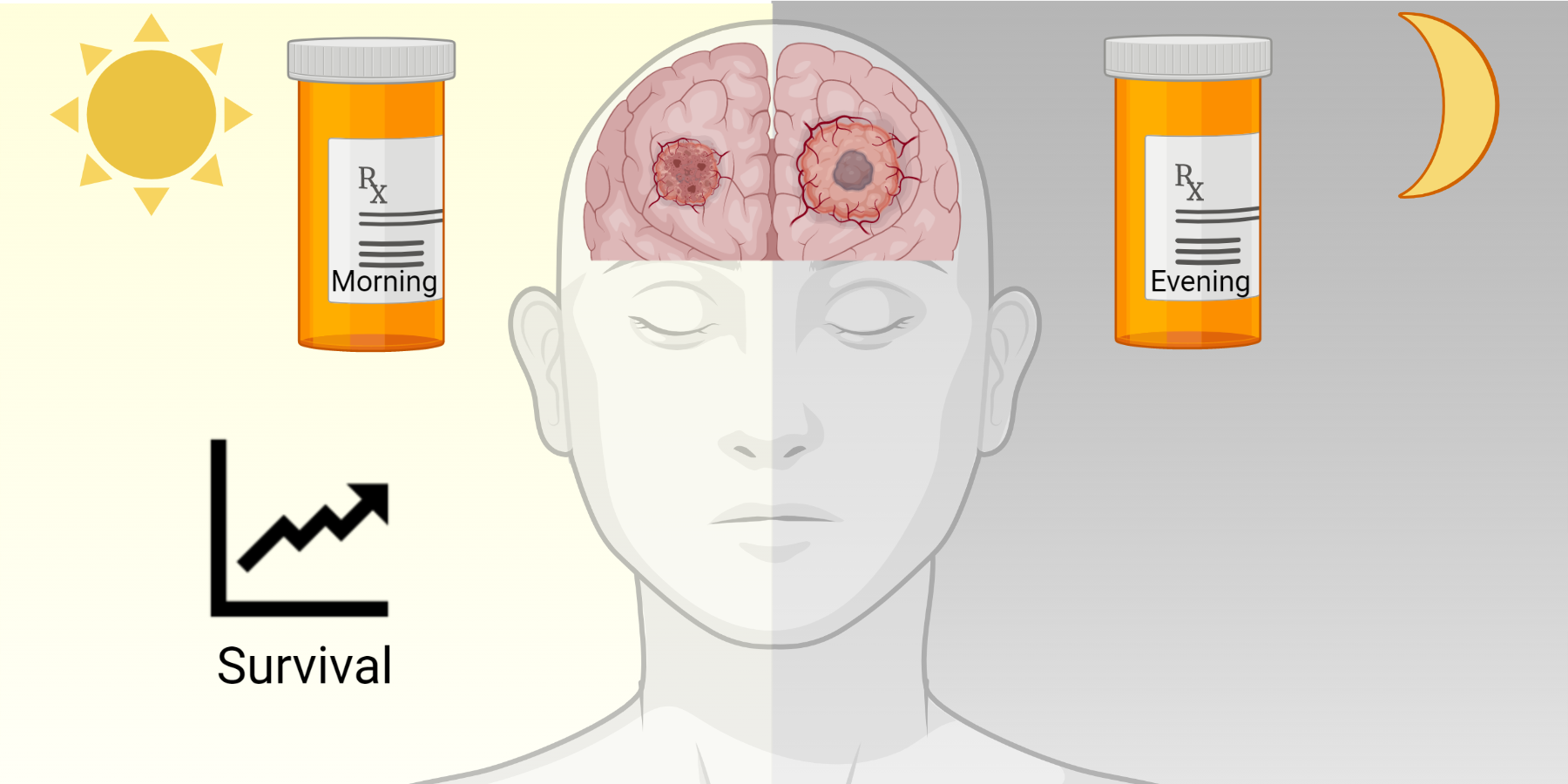

The body’s circadian clock reminds us when to go to bed and when to wake up. Now scientists at Washington University in St. Louis have published findings showing that there may also be a more ideal time to take medication – at least in patients suffering from glioblastoma.

PC: Anna Damato

In work published in Neuro-Oncology Advances, senior authors Erik Herzog, the Viktor Hamburger Distinguished Professor and a professor of biology in Arts & Sciences; Joshua Rubin, a professor of pediatrics and neuroscience at the School of Medicine; and Jian Campian, an associate professor of medicine at the School of Medicine, found that giving chemotherapy to glioblastoma patients in the morning instead of in the evening extended survival by a few months.

“In my lab, we were studying daily rhythms in astrocytes, a cell type found in the healthy brain. We discovered some cellular events in healthy cells varied with time of day. In collaboration with Dr. Rubin, we previously found that glioblastoma cells also have daily rhythms, including in their sensitivity to chemotherapy. In this retrospective study, we asked if time of day of treatment impacts patient outcomes,” said Herzog.

Co-first authors Anna R. Damato, a graduate student in neuroscience in the Division of Biology & Biomedical Sciences working in the Herzog lab, and Jingqin (Rosy) Luo, an associate professor of surgery in the Division of Public Health Sciences and co-director of Siteman Cancer Center Biostatistics Shared Resource, analyzed data from 166 patients with glioblastoma who were treated at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine between January 2010 and December 2018.

When looking at all of the patients in the study, Damato and Luo found that receiving the chemotherapy drug temozolomide in the morning extended survival by 3½ months. In a subset of 56 patients with MGMT methylated tumors, the average survival increased by 6 months when temozolomide was given in the morning.

These results encouraged the authors.

“There have been screens of different drugs given to cells at different times of day, and huge percentages of these drugs are shown to have time-of-day dependent effects on cell survival. For example, how the drug is absorbed might change throughout the day,” explained Damato.

“Yet, very few clinical trials consider time of day even though they target a biological process that varies with time of day and with a drug that is rapidly cleared from the body,” added Herzog.

To confirm the promising results of the retrospective analysis, the researchers are conducting a clinical trial in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients who either receive temozolomide in the morning or evening.

“We will need clinical trials to verify this effect, but evidence so far suggests that the standard-of-care treatment for glioblastoma over the past 20 years could be improved simply by asking patients to take the approved drug in the morning,” said Herzog.

Read the full press release from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and more about the clinical trial in Curiosus.