“Healthy soils are a natural resource,” said Brian Gallagher, a third year PhD student in the Plant and Microbial Biosciences Program. He is part of a team from the Bose Lab that received a Here and Next Grant for their project, “Engineering targeted Soil Microbiota Transplants for restoring health of depleted agricultural soils.” This research will look at the ways soil heath in Missouri can be improved using the microbiomes of natural Missouri soils as a template and as a donor.

The soil microbiome, that is, the community of tiny organisms called microbiota that live in the soil, contribute to everything from nutrient cycling to crop fertility. In other words, the microbiome is important not only for the soil, but also for us. Problems arise when we deplete the soil through things like monoculture farming and pesticide use. “We don’t want another dust bowl situation,” Gallagher said. “We need to think long term, about how generations after us will continue to farm the same soils and feed the global population into the indeterminate future.”

This grant builds off of Gallagher’s Danforth Seed Grant, which he received as a graduate student PI in fall 2023. Now, with this additional funding, Bose’s team will be able expand the project. “Having the money from the Here and Next grant will help us build collaborations as we look toward submitting a competitive proposal to USDA this fall,” Gallagher said.

The team from WashU consists of PI Arpita Bose, Associate Professor of Biology, co-PIs Joshua Blodgett, Associate Professor of Biology, Fangqiong Ling, Assistant Professor in the McKelvey School of Engineering, and Christopher Topp from the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center.

Joining the WashU-Danforth team are outside collaborators, including Frank Nelson with the Missouri Department of Conservation and Kyle Steele from the United States Forest Service. The issue of soil health is relevant to a wide range of researchers and professionals, as well as stakeholders in the broader populace like farmers and conservationists. The Bose Lab wants to bring together an interdisciplinary team to study the soil microbiome and how we can leverage it to help save our soils.

The Here and Next funded research led by Bose and her team is centered around the soils of Missouri’s unique Ozark fens, whose microbial communities are unstudied. “We don’t know what these communities look like, which microorganisms are living there or what they’re doing,” Gallagher said. “There have been studies of other fens elsewhere in the world, and of other wetland soils here in Missouri, but they’re not really comparable to these unique ecosystems.” These soils are different from many other types of wetlands because they are fed by groundwater, something that’s possible because of the karst topography of the state. The first part of this project involves trying to understand the fen microbiome—what’s living there, and what are they doing that helps make these soils so healthy?

The Missouri fen soils are ideal for this research because they share, as Gallagher put it, “the same local conditions” with the immediate surrounding area. “If it rains on the fen,” he said, “then it’s raining on the agricultural soils next door.” Soils, he explained, can change dramatically even over a short distance. The fen soils are therefore a good comparison point for nearby land.

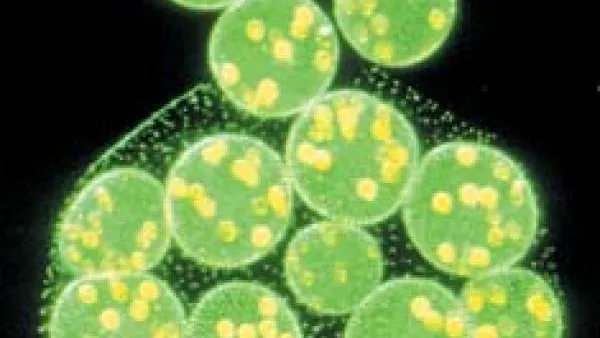

These soils are also ideal because of their health: “They naturally assimilate nutrients from the atmosphere through the actions of bacteria,” Gallagher said. “They have a lot of plant life and biodiversity without the introduction of things like fertilizers, and they have the microbes to thank.” Additions like fertilizers are a quick fix to a much bigger problem, and they end up hurting the soils in the long run by damaging their native microbial communities. Part of what makes these fen soils so successful without those additions is the complex ecosystem of microorganisms that make up their microbiome. “The thing about ecosystems is that they don’t usually have just a single member,” Gallagher explained. “So, introducing just one microbe won’t get the job done— at least, not in the stable, long-term way we want. You need a community.” That’s where the second part of this project will come in, as the researchers use the insights gained from studying the fen ecosystems to engineer microbiota-based treatments to improve soil health.

This project is different. “We’re developing smaller, more manageable communities where we can characterize every member of that community,” Gallagher continued. This includes members like the free-living bacteria that perform nitrogen fixation in the soil. “They’ll be able to grow together as groups, even if some can’t be isolated.”

These microorganisms will then be inoculated into depleted, unhealthy soils. “Put simply, we’re making probiotics for dirt,” Gallagher said. Like with probiotics, the goal of these inoculations will be to improve the health of the host by improving their microbial community. In this case, the host is the soil. Gallagher called it a sort of “precision medicine.”

The impact of this research will go far beyond Missouri. As demand for food increases with a growing global population, so will the demand for healthy, productive soils. Gallagher hopes that this project will serve as an inspiration and a template for others like it. Every soil community is different, but this research shows the benefits of looking at the problem from a more holistic point of view. “We’re killing our soil, but we don’t have to be,” Gallagher said. “Preserving soil health and intensifying agriculture production don’t need to be mutually exclusive.”