Assistant Professor Andi Kautt decodes the science of smell and survival in Missouri's tiny residents

Out in the wild of Shaw Nature Reserve, it’s quiet enough to hear a mouse. That’s a good thing for Assistant Professor Andi Kautt and his team who are spending their morning with these little creatures and their keen sense of smell.

Shaw is the perfect place to catch a mouse—or several—with multiple types of habitats existing just a few steps away from one another. On a hot summer day, Kautt’s team set sixty traps in total here at the reserve—twenty in the glade, twenty in the forest, and twenty in the prairie. The following morning, the glade proves to be the most successful spot.

With the help of Lab Manager Kristina Ottens and undergraduate researcher Trey Ochs, Kautt sets up three portable, enclosed arenas, each with a different smell: one with the scent of a fox, one with a strong non-predator odor that leans more minty, and a water control. By observing their reactions, the team hopes to understand how predator pressure, mediated by the sense of smell, shapes mice behavior in the wild. A small infrared camera captures how they move and react, allowing us humans a glimpse into a world we usually don’t get to see.

These reactions aren’t something the mice have picked up over the years. “They are innate behaviors,” Kautt explains. “That’s the cool thing about the system: it typically doesn’t require learning.” In other words, a mouse’s environment has less impact on their response to predators than their genetics. It’s the way they’re wired. “The question is, do individuals, populations, or species differ in their behavior,” Kautt continues. “If so, can we identify the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying this variation.”

Originally trained as an evolutionary biologist working with cichlid fish, Kautt now leads a team that focuses on ecologically diverse local species like these deer mice to explore some of the most fundamental questions in biology: How do species diversify? How do they adapt to new environments? And how does behavior influence that process?

One part of that puzzle is playing out right here in the tall grasses of Missouri, everywhere from Shaw Nature Reserve to Tyson Research Center.

Bringing the wild into the lab

Complementing the research in the field, where Kautt can observe behaviors in semi-natural conditions, is a large laboratory component that involves DNA sequencing, molecular experiments, and controlled behavioral tests. The combination of these approaches allows Kautt and his team to get a more complete picture of how an organism’s genetics connect to phenotypic variation, behavior, and evolution.

But anti-predator behavior is only one part of this project. The research also investigates how the two species of deer mice found throughout Missouri—Peromyscus maniculatus and Peromyscus leucopus can coexist. Despite looking nearly identical, the two have distinct preferences: one for open grassland, the other for wooded areas. “Given the patchy distribution of forests and prairies in Missouri, this begs the question: how do these mice choose their habitats? How does a forest mouse know it’s better adapted to the forest than the prairie and vice versa? How do they distinguish between a potential mate and a heterospecific?” Kautt says. His team is using behavioral data, habitat surveys, and genomic tools to identify each species and even screen for potential rare hybridization events.

After the wild mice are done in the arenas, Ottens takes over to gather even more information, including a small tissue sample along with the sex and weight of each mouse. That sample will go back to the lab for genetic sequencing. It’s only then that Kautt will confidently be able to distinguish between the two species present in the area.

Important invertebrates

Luckily for Kautt, deer mice aren’t the only unconventional creatures that call Shaw Nature Reserve home. Crayfish, the state invertebrate of Missouri, are hiding just below the surface.

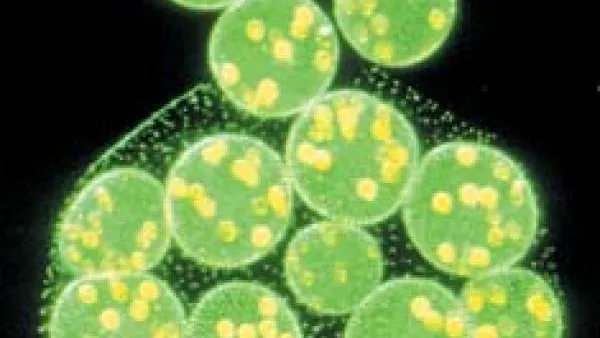

Kautt’s team is working to generate whole-genome assemblies for all 41 crayfish species in the state. With that genomic data, their first goal is to build a robust evolutionary tree to better understand how crayfish have diversified across Missouri. “Some crayfish live only in pristine streams, while others prefer swamps and roadside ditches. Some crayfish spend most of their lives underground in large, elaborate burrows, while some can only be found in caves,” explains Kautt.

Obtaining tissue samples for all species is an effort spearheaded by naturalist and graduate student Shiyang Wu, and only possible through close collaboration with the Missouri Department of Conservation. The questions that drive this research are about ecomorph evolution, historical bottlenecks, and evolutionary relationships. Undergraduate Ellie Wang spent her summer training a machine learning model to recognize crayfish, paving the way for automatic tracking and behavioral assays. Luckily, crayfish, just like deer mice, can be observed locally and brought back into the lab, making them ideal for this type of research.

An unconventional future

These projects are only the beginning of what the Kautt Lab has in store at WashU. Kautt envisions setting up local crayfish as a new system for evolutionary genomics and behavior research. Future studies involving deer mice will continue to dig deeper into the role of smell-mediated behaviors, their genetic underpinnings, and the molecular mechanisms that translate the genetic variation to differences in how animals behave, be it to find suitable habitat and food, potential mates, or to avoid predators. “You know, the essentials, if you’re a mouse” says Kautt.

Ultimately, though crayfish and mice may seem unassuming and unrelated, Kautt is nonetheless excited about what these nontraditional model organisms can teach us about ourselves and the land we share “The value of this research is twofold,” Kautt says. “First and foremost, these little creatures will help us uncover some fundamental biological processes. But deer mice and crayfish are also important parts of their respective ecosystems, and our research has real-world implications for conservation policies, which ultimately benefits all organisms inhabiting Missouri, including us.”