In 2018, an E.coli outbreak struck romaine lettuce. Supermarkets pulled romaine lettuce from their shelves. Restaurants stopped offering Caesar salad. Reading the news reports left many of us worrying about that last meal we consumed involving romaine lettuce. The outbreak lasted four months. 210 people were sickened, 96 people were hospitalized, and 5 people died.

It takes the CDC days to diagnose infections when bacteria contaminate food products. But what if it only took a few hours? Could we minimize the impact of the outbreak on human life?

“Before we started working in diagnostics, we were pretty shocked when we learned that culture-based methods are the gold standard for a lot of tests. It is 2019 and it seems antiquated to grow organisms for weeks from a saliva, blood or stool sample before we can tell patients what the organism is that is making them sick,” said Lucas Harrington, who graduated from Washington University in St. Louis in 2013 and is now a Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer at Mammoth Biosciences.

Mammoth Biosciences, a biotechnology company based in San Francisco, California, has developed a diagnostic use for the powerful CRISPR technology that has the potential to replace culture-based methods for microbe detection. In other words, it would take hours - not days - to identify E.coli as the culprit responsible for the romaine lettuce outbreak. And possibly save lives.

From undergraduate student to CRISPR expert

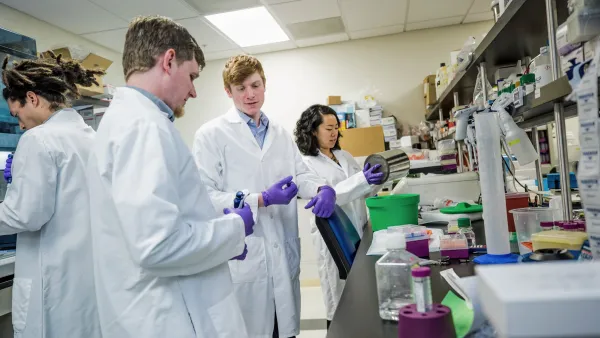

In 2010, as a Washington University undergraduate student Lucas could be found most likely in the lab – the lab of Biology Professor Robert Blankenship – doing experiments. During incubations, he worked on his homework assignments for class. Fast forward to 2019, Lucas, now a Ph.D., still spends most of his day in the lab. Except now instead of doing the experiments, he manages a team of scientists who are working to enable the use of the powerful CRISPR technology for disease diagnosis.

“CRISPR is an incredible tool that comes from a bacterial immune system,” said Lucas.

The CRISPR system protects bacteria from viral infection. It keeps a record of the viral genetic material encountered by the bacterial cell during a viral infection. In future infections, the CRISPR system will attach to and cut a specific viral genetic sequence – one that it had previously seen. Once its genetic material is cut, the virus can no longer replicate itself inside the bacterial cells.

Since its discovery in 1993, scientists from around the world have been working tirelessly to understand these bacterial immune systems but it wasn't until 2012 that researchers recognized CRISPR’s genome - editing potential. Gene editing or the process of deleting or inserting genetic material in an organism’s genome would require scientists to remove the CRISPR system from bacterial cells and insert it into other organisms.

“CRISPR has been repurposed to make very precise changes in almost any organism,” continued Lucas.

The CRISPR system involves an enzyme that can cut genetic material and a sequence that guides the enzyme to a specific genomic location. Scientists isolated the enzyme from two bacterial species. They were able to insert the enzyme into mouse and human cells and guide it to a specific location of the mouse and human genome. The result: the enzyme cut the genetic material in the exact location that the scientists wanted.

“Back in 2014, applications with CRISPR were limited to just a handful of the tens of thousands of CRISPR systems that exist in nature,” explained Lucas. “We were just starting to understand how expansive CRISPR is, leaving much of the potential of this diversity untapped.”

“Back in 2014, applications with CRISPR were limited to just a handful of the tens of thousands of CRISPR systems that exist in nature,” explained Harrington. “We were just starting to understand how expansive CRISPR is, leaving much of the potential of this diversity untapped.”

During that time, Lucas was a graduate student in the Molecular and Cellular Biology program at Berkeley in Jennifer Doudna’s lab - one of the leading labs in the CRISPR field. He became interested in finding new CRISPR systems with features that would improve upon CRISPR’s genome-editing capability.

“To do this we looked at a lot of metagenomic data,” said Lucas.

In other words, Lucas sequenced the genetic material of organisms living in their natural environment, such as in hot spring water or sewage. He found new CRISPR systems that are smaller, tolerant to high temperatures, and have fewer targeting requirements. These features allow for easier and more efficient CRISPR delivery into a wider breadth of organisms when using CRISPR as a gene-editing tool.

Lucas had a prolific graduate career. He published many scientific papers in high impact journals. But it was one discovery in particular that led him to start a company.

Unleashing CRISPR’s diagnostic application

While working on his Ph.D., Lucas and other members in the lab discovered that the CRISPR system has another ability.

After locating and cutting a precise region of genetic material, the enzyme can cut a second genomic region – this time without a guide telling it where to go.

The team realized that the second sequence could be a reporter molecule – a molecule that when cut by the CRISPR system would change color. A change in color would signal that CRISPR found its target – the genetic material of interest.

“We mix all of these reagents and the CRISPR system goes and finds the sequence we programmed it to find and sends out this molecular beacon that lets us know that the sequence has been identified,” explained Lucas.

The idea of using the CRISPR system as a diagnostic tool was born – and so was Mammoth Biosciences. The company, now employing 23 people, is divided into two scientific teams with Harrington leading one of the groups.

At a very low cost and with little time, Mammoth Biosciences can harness the power of the CRISPR system to detect cancer or infectious disease in minutes. Their technology is accurate and rapid. Ultimately, Mammoth Biosciences aims to put out a product that could be used at home and contain a simple read-out system like that seen in pregnancy tests.

“The power of this system is its simplicity and that it can be deployed directly to consumers. The challenge is making sure the consumers are educated properly – not just on how to perform the assay but on how to understand the results,” explained Lucas.

“The power of this system is its simplicity and that it can be deployed directly to consumers. The challenge is making sure the consumers are educated properly – not just on how to perform the assay but on how to understand the results,” explained Harrington.

“We are talking to ethicists and genetic counselors to understand the consequences of the information,” continued Lucas.

Endless possibilities

Mammoth Biosciences has the potential to use its CRISPR-based detection platform across industries. The possibilities are numerous. They have the potential to change how we detect disease in human health. They can also change how we think about plant and animal pathogens in the agricultural industry, our response time to disease-causing organisms in our environment, and even how we detect harmful biological agents in bioterrorism.

“We can go after anything that has a genetic basis,” summarized Lucas, “We are driven by the research and getting CRISPR out into the world. These tools are too powerful to not let them be used.”