The human brain loves to untangle a mystery. Sometimes surprises are part of the process, and journeys lead to unexpected discoveries, such as the findings of Biology Professor Hani Zaher’s recent paper on ribosome speed and cell stress response.

“The coolest part of this paper is that it was an unanticipated discovery. This is what I love about this job. We have a hypothesis, we do the experiment, realize we were wrong, but discover something completely unexpected. In this study, we discovered a new way for cells to activate stress response by messing up the ribosome speed,” Zaher said.

DNA contains the information to make proteins, which are the workhorses for the cell, carrying out functions it needs to survive, adapt, thrive, and divide. But that information is useless if it can’t be accessed. The ribosome’s job is to find and decode this information.

Between DNA and protein, there's RNA in the form of messenger RNA (mRNA), which acts as a transcript. The mRNA has the recipe that the ribosome needs to make a proper protein. The mRNA is floating around, and the ribosome has to reach it. mRNA, has a specific decorative cap that tells the cell this is an RNA that needs to be translated, or decoded, for the ribosome. There's a factor that recognizes that cap in humans—and all eukaryotes—called eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E). Its job is to find that cap structure and latch onto it.

“You need a factor that recognizes that decoration on mRNAs, which then recruits the ribosome to that RNA. The question we asked was very simple: What happens to the ribosome function or translation when that 4E factor is inactivated? When you cannot find the cap structure, what sort of RNAs are still able to be translated?” Zaher said.

Lab members Kyusik Kim and Nanja Urs were trying to understand and identify RNAs whose translation is insensitive to the lack of factor 4E. In yeast cells, they made a mutation that allowed them to decrease the 4E concentration down to 2%. When they looked at the proteins being translated, a lot of them were part of an integrated stress response. Puzzled, the research team worked toward describing a model to explain what happens when 4E is depleted.

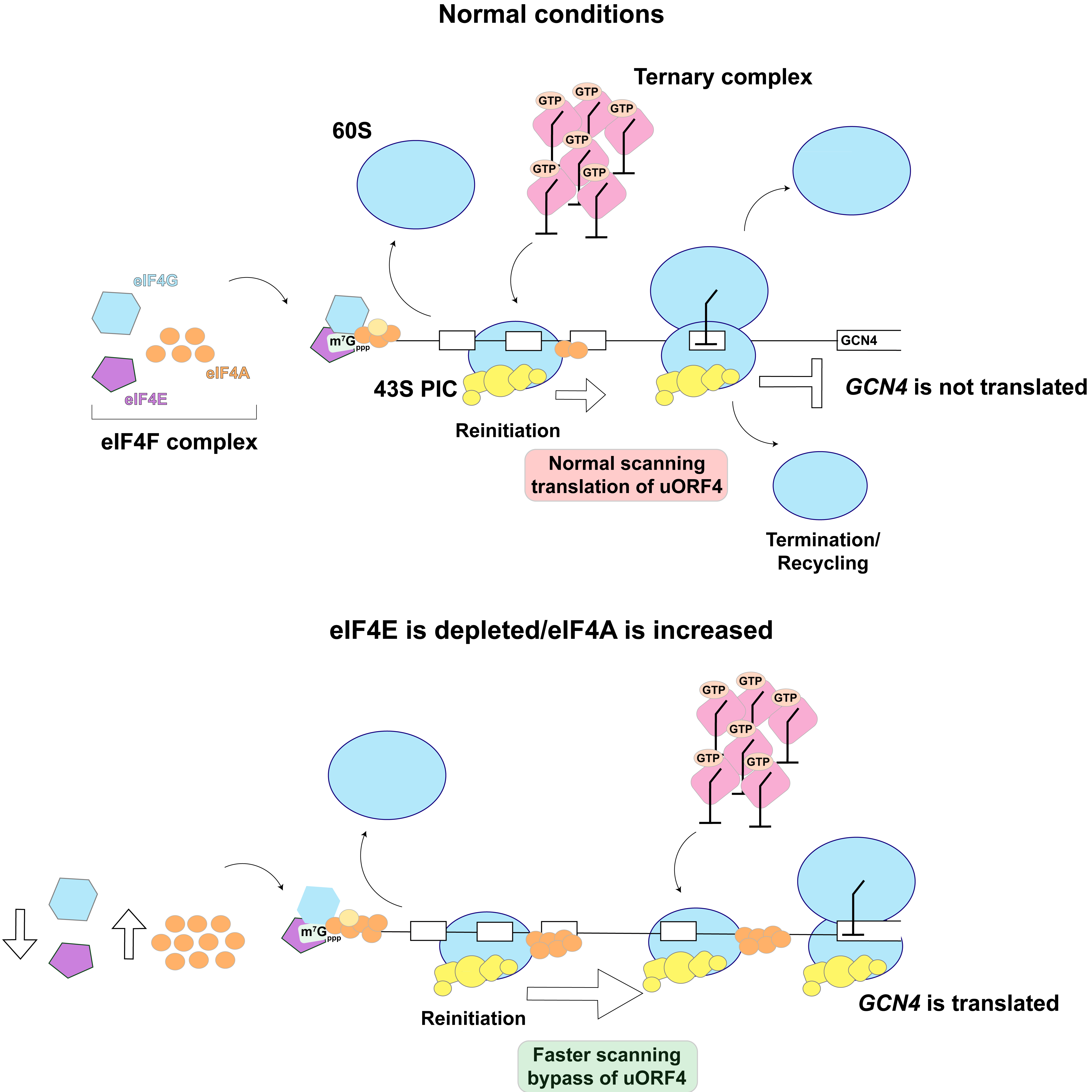

When the ribosome is recruited to the mRNA, it has to move forward slightly through an untranslated region (UTR) to find a signal to start protein synthesis. Then there are stop signals upstream of another UTR. The piece between the start and the stop is called the coding sequence or CDS.

The stress-activated gene, called GCN4, is different from a regular gene. It has that decorative cap and multiple initiation codons, with one main CDS. The ribosome has very easy instructions to follow: scan, find the start signal, translate, find the stop signal, fall off. This mRNA is always around, ready to be translated. But under normal conditions, the ribosome never gets to the main CDS because of the upstream CDS regions. Under stress, the ribosome is able to bypass these CDS regions.

Why is the ribosome able to bypass those when 4E levels are decreased to 2%? When the eIF4E levels are down, there's another factor whose relative concentrations to eIF4E go up. This protein, which helps the ribosome to move through the UTR, is called eIF4A, a partner for eIF4E. This allows the ribosome to move at a much higher speed, allowing it to bypass the short inhibitory CDS regions and land on the main CDS.

The big conclusion of the paper is that relative concentration of these two factors are important for the translation of GCN4. How is that? Why is that? Why should we care?

“We care because we are interested in translation, and in the fundamental process of how the ribosome carries out its function. We conjecture that in certain cancers, you could modulate the concentration of these two factors to modulate the stress response. One of the key things that cancers experience are amino acid starvation. It would make sense for these cells to have a stress response already activated, because that allows them to make the amino acids they need to survive and be more competitive in dealing with that stress.”

“There are clinical trials studying whether inhibition of eIF4A can be used as an anti-cancer therapy, it is possible that by inhibiting eIF4A you inhibit the ability of tumors to activate stress signaling” Zaher explained.

The exciting thing about the lab’s findings is that cells think they're under stress (by depleting the 4E), so they activate pathways to make more amino acids to defend themselves, but they’re not shutting down protein synthesis in the process. In other words, you can have this stress response without shutting down the cell.

“Activating stress response can be detrimental for the cell because it slows everything down. You want it to be activated when you need it, because if you activate it prematurely, it'll put you at a disadvantage, and you'll grow more slowly. Imagine sounding tornado warnings when there's no tornado, causing panic, disruption, and decreased productivity. You wouldn’t want to sound those warnings all the time,” Zaher explained.

Learn more about Hani Zaher and his lab’s research HERE.