Anna Yang, a high school student working in the Bose Lab, won the S.-T. Yau High School Science Award. Founded in 2008 by the master mathematician Prof. Shing-Tung Yau, the S.-T. Yau High School Science Award inspires scientific innovations and is designed for high school students all over the world. Advocating innovative thinking and collaborative spirits, the Award dispenses with paper-delivered test format or standardized test answers and instead gives students the opportunity to participate by submitting academic papers. The Award aims at promoting the development of science education in high schools, stimulating students’ research interests and innovative capabilities, as well as discovering and cultivating young talents in scientific disciplines.

Anna Yang is a current senior at Milton Academy (Milton, MA) passionate about laboratory research in various fields such as biochemistry and molecular biology. She is especially interested in microbial-environmental interactions and using bioengineered microorganisms to combat the energy crisis. Inspired by the current problems in the biofuel production industry, she hoped to develop a more efficient way of producing a biofuel known as ethanol by genetically engineering yeast cells and restructuring their metabolic pathways.

She initiated a research project during the pandemic that focuses on efficiently synthesizing a potential biofuel, ethanol, by creating a new strain of baker’s yeast that optimizes yeast’s natural fermentation process. Last spring, Anna conducted her experiments at the Bose Lab, working alongside students, faculty, and staff at the university.

Yang's summary of her project:

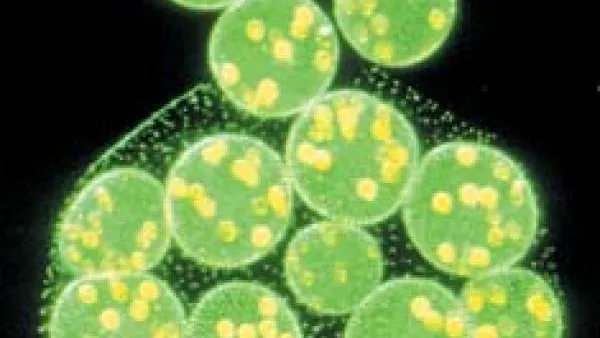

Ethanol synthesized by S. cerevisiae, commonly known as baker’s yeast used in the making of bread and wine, could also serve as a renewable fuel to limit fossil fuel combustion. In yeast, ethanol is produced through the process of fermentation, a metabolic pathway that yeast employs naturally, particularly when oxygen is limited.

Studying the use of ethanol as a renewable fuel holds great promise, but one limitation has impeded progress — ethanol is harmful to cell growth. Other scientists have conducted similar studies in the past. However, historically, mutant strains were shown to increase ethanol production by only up to 40%, according to a 2017 study (1). This is because we simply cannot expect cells to keep producing something that kills them. To surpass this seemingly insurmountable roadblock, we need to increase cells' ethanol production and tolerance simultaneously.

But how? To mutate yeast cells, I used CRISPR-Cas9, a molecular gene editing technique, to knock out a gene called pda1, which codes for an enzyme called pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). PDH is located at the entrance of the citric acid cycle, acting as a “gateway” to aerobic respiration. By disrupting PDH function, we are essentially telling the cells to “ferment all the glucose they consume.” Growth curves and ethanol quantification assays suggested that, consequently, the mutant is deficient in growth, but produces a higher amount of ethanol in exchange. The mutant also demonstrated heightened ethanol tolerance, surviving almost three times better than the wild type when grown in media containing ethanol. I concluded that the combined effects of metabolic redirection and ethanol tolerance may have contributed to the mutant’s high ethanol production.

By creating and studying this PDH-deficient mutant yeast strain, I demonstrated that pda1 is an important regulator of cell metabolism, particularly of ethanol fermentation. By targeting this crucial gene, I increased ethanol production by 66% — a significant advancement in the field of renewable fuel synthesis. Now that we have found a way to genetically modify yeast to produce ethanol, we hope to see renewable energy become more prevalent in the future. This is only the first step; there is much more that we can do.

Link to Yang's paper:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/17vNz_Ul5NxFtB0qDCK2I2dRCHfAwe06P/view?usp=sharing

"It was extremely hard to find a lab willing to take in a student at first, especially during Covid-19. I had to switch labs halfway and ended up conducting the majority of my experiments at the Bose Lab at Washington University in St. Louis. I've reached out to countless labs over many months, but the PI at the Bose Lab was particularly helpful, inviting me to conduct my experiments right when Covid restrictions lifted in March."

"When the whole research industry slowed in the past year, it was hard to finish my experiments and even more so, to get my paper reviewed and published. My research continued for a lot longer than I planned -- with repeated trials and challenges in transporting a new strain, I spent two full years working on the project. In hindsight though, all the hard work felt very rewarding and worthwhile. I'm very proud to have pushed through during the most difficult time for conducting laboratory research as a high school student. It was genuinely a pleasure to be recognized as a Regeneron Scholar. I'd never even thought I'd have the opportunity to join the group along with Nobel Prize-winning STS alums. More importantly, I'm just so happy to have contributed my part toward the advancement of biology and the production of renewable fuels, however minuscule my findings may be in the broader landscape of science. I am very grateful, and I'm feeling even more encouraged now to pursue new research projects and ask more ambitious questions in my scientific career ahead. I hope to keep studying how tiny cells can function as instruments used to solve larger issues such as climate change and human health," Yang said.