It may be challenging to imagine, but there was a time before personal computers. Scientific papers and grants were written out longhand, and a pool of administrators sat in an office space in Rebstock Hall, deciphering illegible writing before typing on a Selectric typewriter. A graphic artist created drawings for paper submissions. Scientists spent hours in the darkroom developing microscopy images on film.

Unlike today where a spacesuit is required for spraying insecticides safely in the greenhouse, there were fewer precautions. The hallways smelled of phenols, and radiation was kept underneath a fume hood with plexiglass shielding the surroundings. Smoking was acceptable everywhere, including the labs, hallways, bathrooms and breakrooms. Everyone smoked.

Department of Biology staff members Dianne Duncan, director of imaging facility, and Michael Dyer, greenhouse supervisor, remember those days as if they were yesterday. That’s because they are celebrating their fortieth working anniversary at Washington University in St. Louis and in the Department of Biology.

Don’t let their perception of time fool you. The state-of-the-art facilities they helped build reflect many years – four decades, in fact – of hard work and dedication.

“I thought I would be working at the university for six months,” Dyer laughed. “We have come a long way.”

The greenhouse, which once occupied a part of the parking lot behind Rebstock Hall, had falling apart screens and a non-functioning cooling system when Dyer arrived in 1983. It also lacked a fertilizer injector system. Exhaust fans had to be set by hand at different temperatures. The heating system came from a main source over which Dyer had little control.

Today, the 10,000-square-foot facility connects to the Life Sciences building; it includes the greenhouse and environmentally controlled growth chambers. Thanks to advances in technology, university and department funding, and Dyer’s years of experience, the greenhouse is lit by state-of-the-art LED fixtures, integrating more light than possible with fluorescent lights. The computer-controlled environments deliver ideal levels of light, temperature, and humidity for growth.

“My days now involve Zoom calls with a technician in British Columbia who is helping us program the controls for the chambers. Everything is synchronized with a weather station,” explained Dyer, who was an agriculture extension agent in North Carolina before coming to WashU.

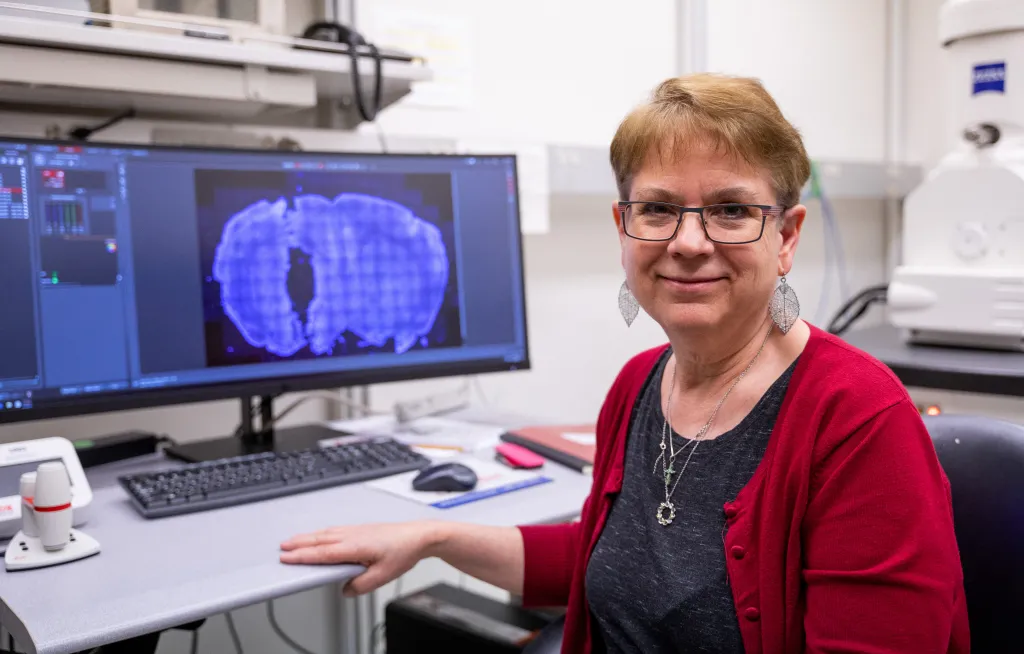

The imaging facility shares a similar history. The room with one microscope has grown into a facility with six microscopes housed in five rooms, putting the biology department’s microscopy core at the cutting edge of image analysis. The newest of a suite of Leica microscopes, the Leica THUNDER Live Cell fluorescent compound microscope, was added in 2021.

Duncan, who took over the facility in 2010, spearheaded an effort to upgrade the older microscopes to state-of-the-art instruments that would run on the same software, and allow researchers to image anything from small animals and potted plants to subcellular details of tissue samples. This effort was made possible by a 2018 award of a sizable NSF grant to procure a multiphoton confocal microscope for the core. The multiphoton then served as the foundation for procurement of three new Leica instruments funded in large part by the department. All of these instruments were installed within the last 5 years.

“I've done a lot of microscopy throughout my career, but, really, I'm a molecular biologist. I wasn't sure I was going to be able to pull off running a microscopy facility,” said Duncan humbly. She joined the university as a graduate student and earned her master’s degree under the mentorship of Professor David Kirk. She was also a staff scientist for many years in the department before directing the imaging facility.

History shows that she pulled it off.

Shared memories

For years there was a stain on the floor of the east stairwell of McDonnell Hall. It was a reminder of the infamous night of the watermelon.

The watermelon, full of fresh fruit, was enjoyed by department members during a gathering. When the fruit was gone, as were most of the people at the party, a few remaining night owls, who will not be named, conducted an experiment to test gravity. The watermelon was dropped from the fifth floor for a free fall down an open stairwell.

The experiment was a success – gravity pulled the watermelon to the ground.

Thud.

Laughter broke out.

It hasn’t all been just work for Dyer and Duncan. They have shared many memories over the years.

Christmas parties took place in the greenhouse. Dyer helped organize them. Members of the department, including Duncan, would sing Christmas carols. Department chair Roy Curtiss III (1983-1993) dressed up as Santa Claus. His long white beard made him a natural choice for the role. Santa never worked alone; he had help from a few department elves. Children of department members joined the fun.

Former payroll employee Saul Becker made cupcakes decorated as snowmen before fancy cupcakes were a thing. Retired computer systems manager David Heyse ran a coffee and Kahlúa bar. Professor Nobuo Suga was well known for his noodle dish. There was always plenty of champagne when Professors Memory and Walter Lewis were around.

Then there were the magic shows. An aspiring magician would light nitrocellulose membranes on fire in the hallway. The magic in that trick was that the sprinklers didn’t go off.

And they definitely didn’t have to wait a full year for a fun social hour. As the end of the week approached, graduate students collected money for beer, soft drinks and snacks. Everyone was invited to join the conversation. People came, and ideas were shared.

It didn’t matter what role you played in the department. “Everyone had a voice. There was no hierarchy,” Duncan explained.

“It’s a great department to work in,” emphasized Duncan, “with supportive people who have made the past forty years fun.”

And interesting.

Duncan recalls looking up at one of the biology buildings on her way into the lab one morning to find a bat on a stick hanging out of the window. The Suga lab was conducting an experiment. If only she had a cell phone to capture the moment.

“See, that is how you end up staying here for forty years. Interesting people keep you motivated. And interesting projects keep walking in the door – or hanging out the window. They keep you engaged,” said Dyer.