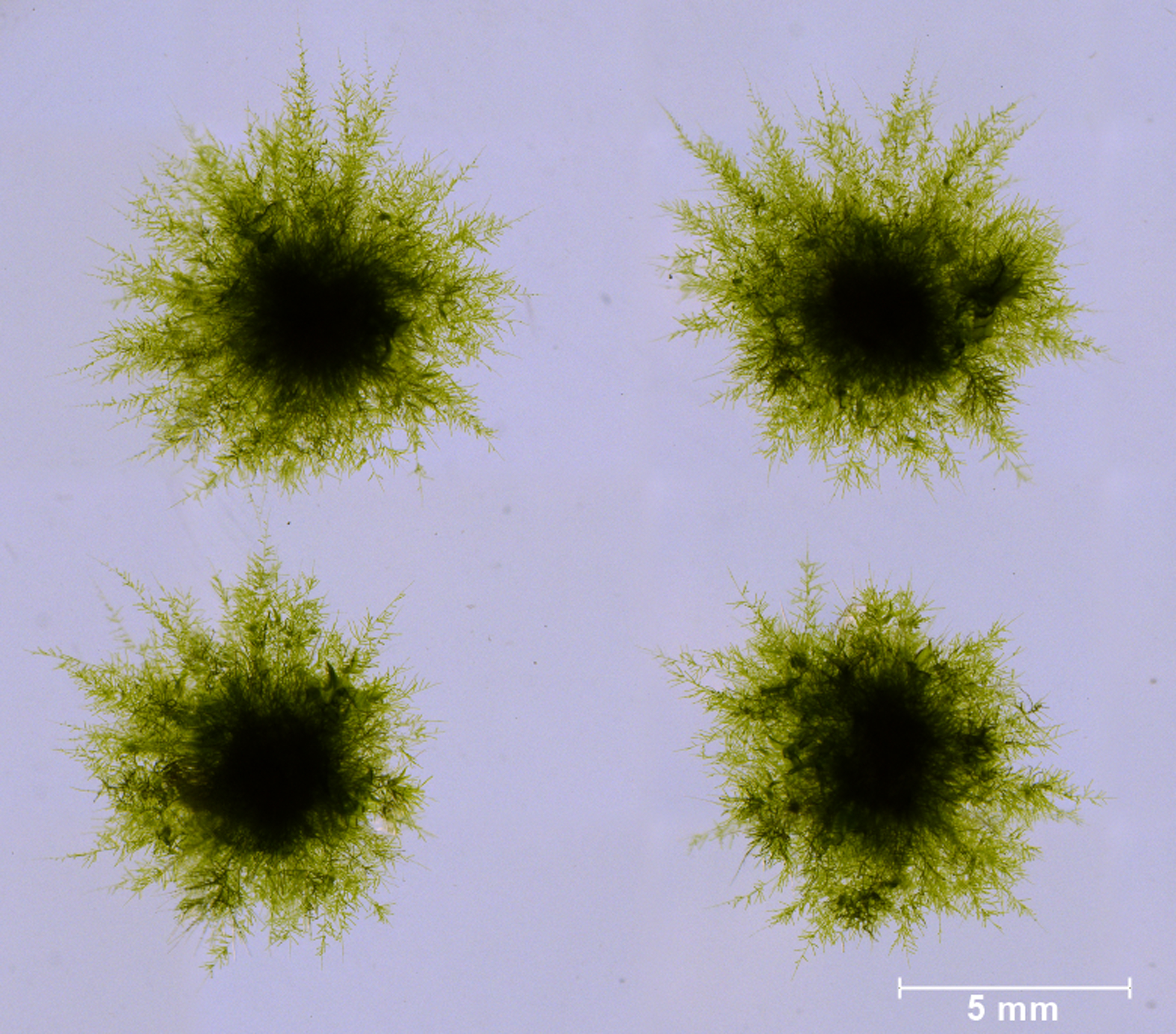

During his professorship in the biology department at Washington University, Ralph Quatrano, now the Spencer T. Olin Professor Emeritus of Biology, became well known for his use of moss or more specifically Physcomitrella patens as a model organism to study the basic mechanisms controlling plant cell and tissue morphogenesis and the gene regulatory networks that control desiccation tolerance in seeds. He was a pioneer in this small, but growing, field of research.

Now Professor of Biology Elizabeth Haswell and her lab are proud to continue the tradition of moss research at Washington University.

“Moss is a beautiful system for studying cell biology. It has multiple genetic advantages for asking complicated questions,” said Haswell.

It can be manipulated easily. It grows fast. The moss dominant life stage is haploid.

“Meaning it has only one copy of each chromosome. Therefore, we can knock a gene out and look at the effect in the next generation. In comparison, in the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana it takes a second generation to see results,” explained Haswell.

Moss is simple to grow.

“They can literally be ground up and they still recover!” continued Haswell.

Ivan Radin, a postdoctoral scholar in the Haswell lab, learned how to grow and genetically manipulate moss while visiting the laboratory of Magdalena Bezanilla, a former postdoctoral scholar in the Quatrano Lab, who now has a lab at Dartmouth University.

“The visit to the Bezanilla lab was an amazing opportunity to learn a lot of little tricks when working with moss and to start a productive collaboration,” shared Radin.

A primary reason the Haswell lab has started working with moss is because of its position on the evolutionary tree as a representative of one of the first lineages to conquer land 500-600 million years ago. This allows them to ask questions about how the traits and proteins they study have evolved and changed over time in land plants.

They realized that the moss model is amazingly practical for the biological questions they have already been asking in Arabidopsis.

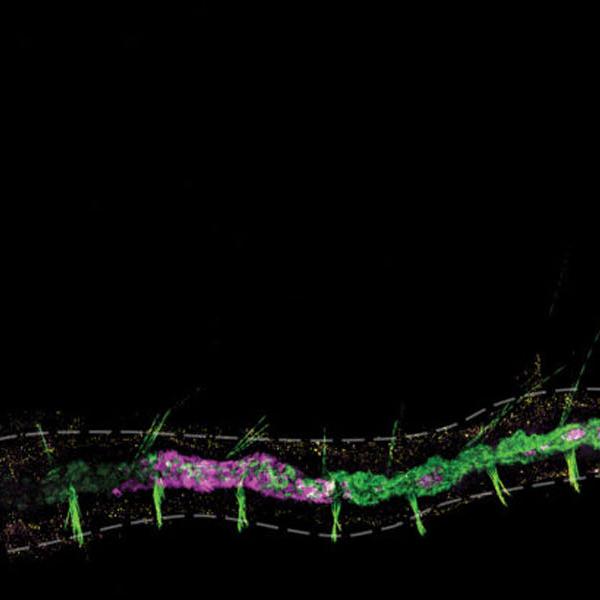

“Our goal is to reveal the molecular mechanisms that underlie the perception and transduction of mechanical signals in plants. The lab’s main focus is how plants perceive mechanical forces on the cellular level, including touch, gravity, and internal changes like swelling or shrinking,” explained Haswell.

“Our goal is to reveal the molecular mechanisms that underlie the perception and transduction of mechanical signals in plants."

They are now starting new projects that will expand their use of moss. These projects involve undergraduate students in research on genetic modifications, where they knock genes that they hypothesize are involved in sensing mechanical stimuli in moss, using CRISPR. Ryan Richardson, a technician in the lab, is overseeing these projects.

“The lab has a workflow plan where undergrads can jump in at any point in gene editing,” said Haswell.

As one of the earliest promoters of moss as a model system, Ralph Quatrano is thrilled to see the tradition of moss research continuing at Wash U.

“I remember when I first met Liz during her interview with the biology department. She presented a very unique research problem, mechanosensing in plant cells. I thought her approach was refreshing, unique and forward-thinking. I value her contribution to this research but also her commitment to the department and the many services she’s contributed,” said Quatrano.